Get Generations Telling Their Stories:

Survey says American kids need to know their grandparents

At first reading, I was surprised by an article in the December 20, 2018 “New York Post,” headlined “One-third of Americans can’t name all of their grandparents.” This finding is from a recent survey of 2,000 Americans commissioned by Ancestry and conducted by One Poll.

Other nuggets:

• 34 percent of respondents can’t trace their family tree past their grandparents, and even that knowledge is incomplete.

• 21 percent of respondents can’t name even one of their great grandparents.

• 21 percent have no idea where any of their grandparents were born.

• 14 percent are unaware of how any of their grandparents earned a living.

But after I stopped to consider the poll’s finding, I realized the headline resonated with me because my father never discussed his parents. I barely knew their names, and I have no understanding or feel for who they were. I would love to have some knowledge of them; especially now that I have two grandsons, age 8 and 5, with whom I am very close. I am lucky to spend time with Finnegan and Wyatt frequently. They know my minutiae, call me silly nicknames, could tell you that my favorite color is green, and my top beach vacation locale is in North Carolina.( They might add that I’ll make them homemade oatmeal cookies whenever they like.)

Conversely, my father’s parents — my own grandparents — died when my Dad was still a teenager. I have one photo of each of them — that’s it.

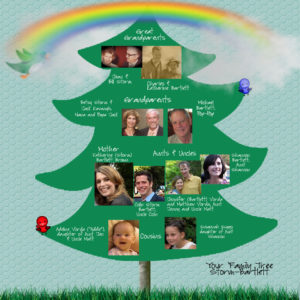

When Finn was born, I created a digital scrapbook for him so that — among other reasons — he will feel a connection to my own parents (long deceased) when he is old enough to ask questions about his roots. When Finn’s brother Wyatt came along, I began a scrapbook for him, too. My favorite page in each of these books is a colorful tree that features both sides of their families, maternal and paternal, side-by-side in a 12” x 12” four-color book format. (See photo.) Someday, I hope and believe these family trees will be meaningful to my grandsons. For example, knowing that both of their maternal grandfathers were award-winning newspaper reporters may make these colorful men more real — and thus more meaningful — to my grandsons when they see the likenesses of these distinguished-looking reporters, Bill Storm and Charlie Bartlett, on their family tree.

When Finn was born, I created a digital scrapbook for him so that — among other reasons — he will feel a connection to my own parents (long deceased) when he is old enough to ask questions about his roots. When Finn’s brother Wyatt came along, I began a scrapbook for him, too. My favorite page in each of these books is a colorful tree that features both sides of their families, maternal and paternal, side-by-side in a 12” x 12” four-color book format. (See photo.) Someday, I hope and believe these family trees will be meaningful to my grandsons. For example, knowing that both of their maternal grandfathers were award-winning newspaper reporters may make these colorful men more real — and thus more meaningful — to my grandsons when they see the likenesses of these distinguished-looking reporters, Bill Storm and Charlie Bartlett, on their family tree.

The good news is, the Ancestry survey respondents want to learn more about their backgrounds. Eight in 10 say they care about their heritage, and they’re willing to learn how to ferret out information that will help them forge a closer connection to their ancestors.

“In recent decades, we’ve seen a major upswing in interest when it comes to researching family history, and this is largely due to the accessibility of historical information,” says Jennifer Utley, director of research at Ancestry.

She continues: “This valuable historical data is helping people paint a picture of their past, and the holidays are a great time to start investigating our own family history.”

“Most family history research starts with oral history, listening to the stories passed down from generation to generation,” says Utley. “Conversations during holiday gatherings can help us discover more than just what country our relatives migrated from, but also who they were as individuals — their stories, their dreams and lessons learned.”

In particular, the survey reports, Americans would like to know the following about their grandparents: stories of them when they were young; childhood memories; their heritage; life advice; their personal beliefs; health issues common to the family; general medical history; what kind of work they did; and best trips/places they’ve experienced.

Betsy Storm Chicago Personal Historian

was a well-known Philadelphia newspaper reporter). Our boyfriends were fast friends, and the foursome we shared still wins top billing among my fondest college memories.

was a well-known Philadelphia newspaper reporter). Our boyfriends were fast friends, and the foursome we shared still wins top billing among my fondest college memories. info@betsystorm.com

info@betsystorm.com  312.401.5222

312.401.5222